Early Years and Education

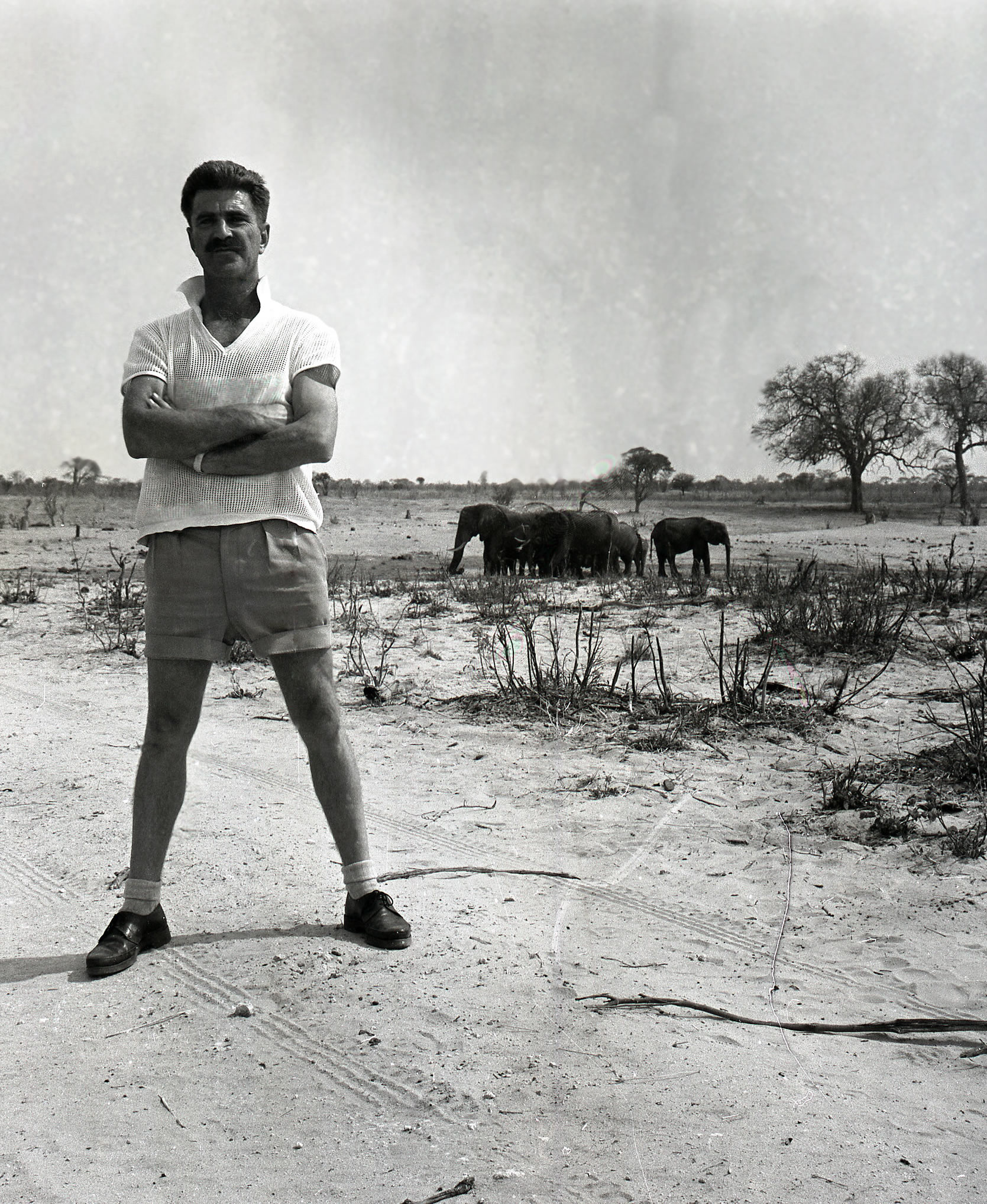

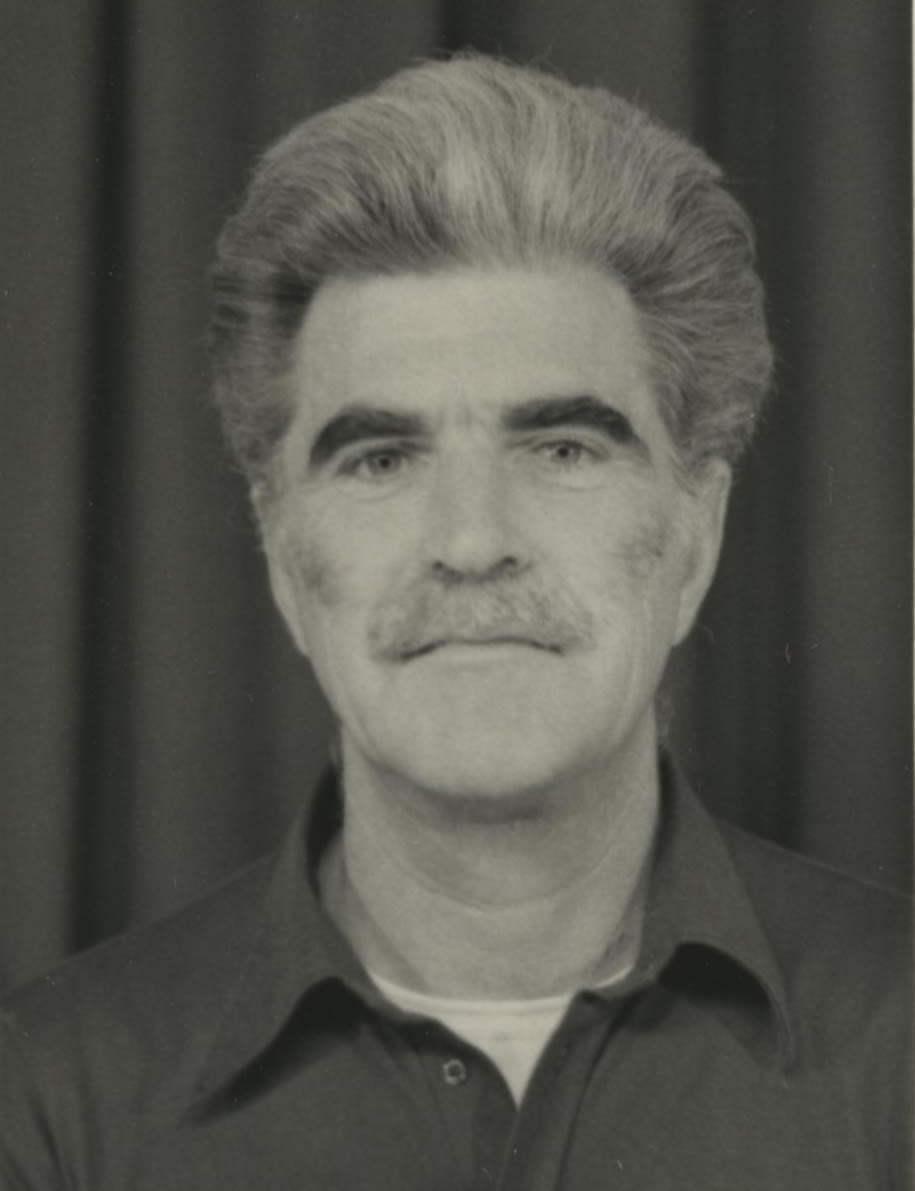

Peter John Sutherland Mackay (31 July 1926 - 17 April 2013) was a British Officer, journalist and key contributor to the African nationalist movement in Central and Southern Africa.

Born in Bow, London, Peter Mackay was the son of Major George Sutherland Mackay (10 July 1895 - 17 March 1976) and Christine Helen Bourne (16 December 1902 - 8 April 1982). His paternal grandfather was the Reverend George Sutherland Mackay, Minister of the Free Church of Scotland in Doune1 for thirty years, and his maternal grandfather was Walter William Bourne who, along with his brother-in-law, Howard Hollingsworth, founded the Oxford Street department store, Bourne and Hollingsworth2 in 1894.

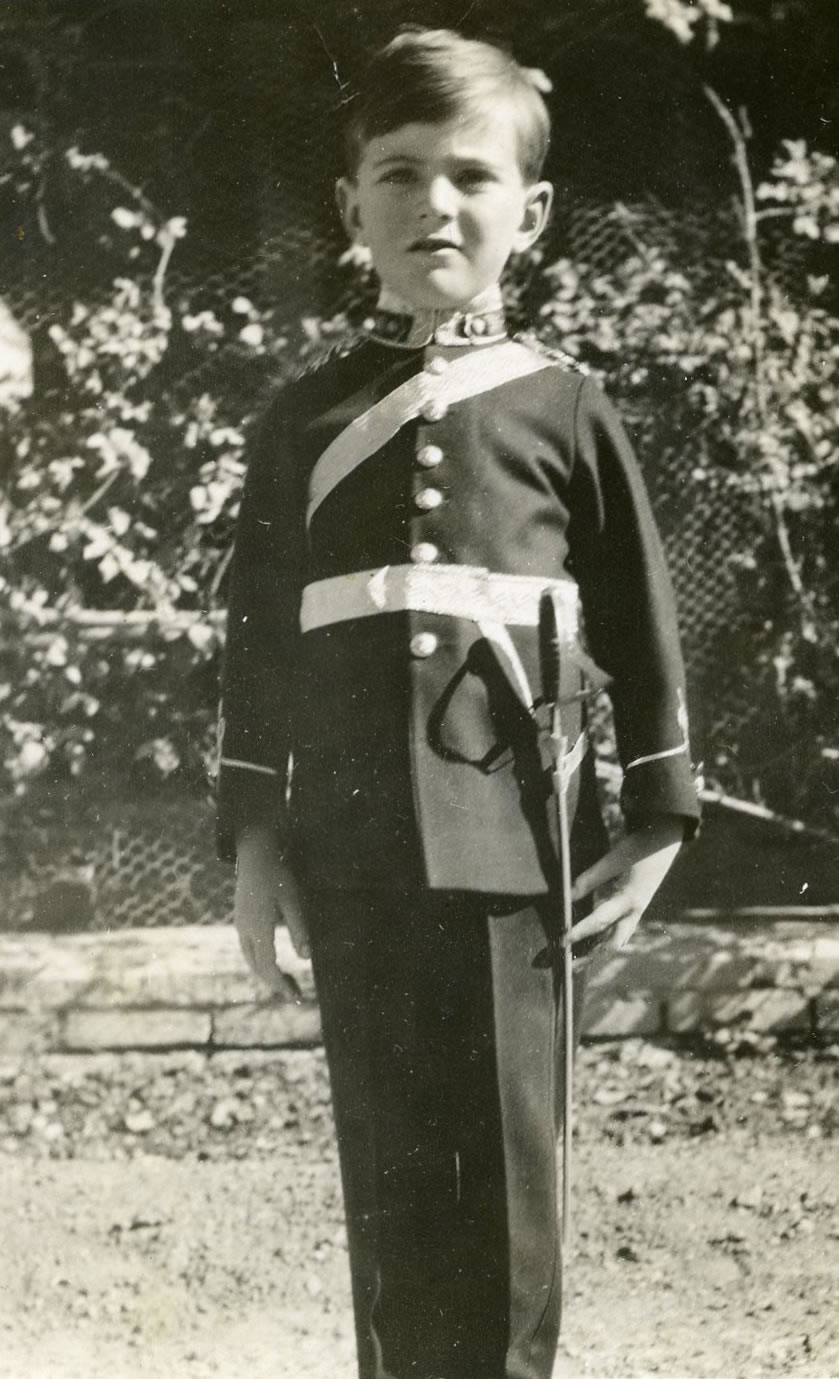

Mackay was educated at Kingsmead and Stowe School, and in 1944 became head boy of Temple House.

Military Career

Mackay was entered for Trinity College, Cambridge but opted instead for military service, enlisting with the Black Watch (Territorial Army) on 13 March 1944 then transferring to Her Majesty’s Scots Guards (Territorial Army Reserve). On 22 June 1945, he was appointed to an emergency commission as 2nd Lieutenant and tasked with escorting German prisoners of war from London. By 1946, at the age of twenty, Mackay had advanced to the rank of Acting Captain and was commissioned as Small Arms Instructor of the Platoon Weapons Wing at the School of Infantry in Kent, and senior small arms instructor of the No 3 Commando Brigade, Royal Marines based in Malta.

With the war over, Mackay was facing redeployment to the Ministry of Defence or ceremonial duties at Buckingham Palace, neither of which appealed to his sense of adventure. After spotting an advertisement in The Times for a tobacco farming apprenticeship under Colonel Herbert Stewart, Mackay was released from military service on 15 August 1948 and granted the honorary rank of Captain.3 He turned down a job with his father at Anglo-Iranian Oil (later British Petroleum) and set off on a multi-stop, five-day journey by air from Malta to Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia to begin his tobacco farming career on the Galloway Estate in Macheke, Mashonaland.

Colonel Herbert Stewart is willing to take four pupils for the coming season to learn cultivation of Tobacco, Mealies and Groundnuts. They will live ‘en famille’ i.e. feed and sleep in the house, share a sitting room set aside for them with servants to attend to their domestic needs. Five guineas covers all extras. Colonel Stewart hopes to take the two best pupils as Assistant Managers for the following season with Salary and Percentage bonus. This will give them an extra year’s experience and he will give every help possible to any pupils at the end of his training to take up a Government Grant of land and start out on his own. But Capital will be required for this. Tobacco is an expensive and exacting crop needing knowledge, experience and close attention.

The Times, 1948

JOURNALISM & POLITICAL ACTIVITY

Mackay was not unique in relocating to Southern Rhodesia during this period. The 1944 Land Settlement Act which allotted farm or Crown Land to ex-service personnel along with loans for the purchase of farming equipment and livestock, and the 1946 Immigration Act, which ensured that new settlers were 'acceptable' (i.e. British-born and skilled), made Southern Rhodesia an attractive prospect. The end of the Second World War brought a massive influx of settlers to Southern Rhodesia, many of whom, like Mackay, were seeking an adventurous, outdoor lifestyle that was in sharp contrast to post-war Britain.4 With his family in the United Kingdom still under rationing, Mackay sent regular food parcels, along with letters, to his mother in which he described the land of plenty with its abundance of food, servants, European clubs and privilege. Mackay was determined to secure his own piece of virgin African soil and hence, his fortune. But his attempts at tobacco farming were thwarted by drought, diseased land and a tobacco tax deadlock and by 1952 he was bankrupt and had to call on his parents to clear his debts. 5

At a loss, Mackay walked into the temporary Salisbury office of the United Central Africa Association (an organisation set up by Southern Rhodesian Prime Minister, Sir Godfrey Huggins, to promote the proposed Central African Federation scheme among the white electorate) and with his characteristic zeal, was soon actively engaged in the campaign. He wrote to his mother about his future plans

I was asked at the end of my three weeks’ temporary, unpaid activity with the association to stay on for a few months. The job is both interesting and worthwhile – in fact it concerns the most important issue which has ever faced the Colony… Federation. Federation is the keystone to Africa’s future and if it does not go through it would be a calamity. There is a tremendous amount of opposition to it and as we are the only organisation backing it up we have our hands full - and, if the truth be known, we are on the losing side at the moment.

Personal Correspondence, 1952

Mackay was proud, but immensely surprised at his metamorphosis from bankrupt tobacco farmer to political activist. He described the Federation campaign as unparalleled, suggesting that if all went well Britain would have the 'embryo of a substitute for the Indian Empire'6 and Rhodesia would be on the threshold of great things.

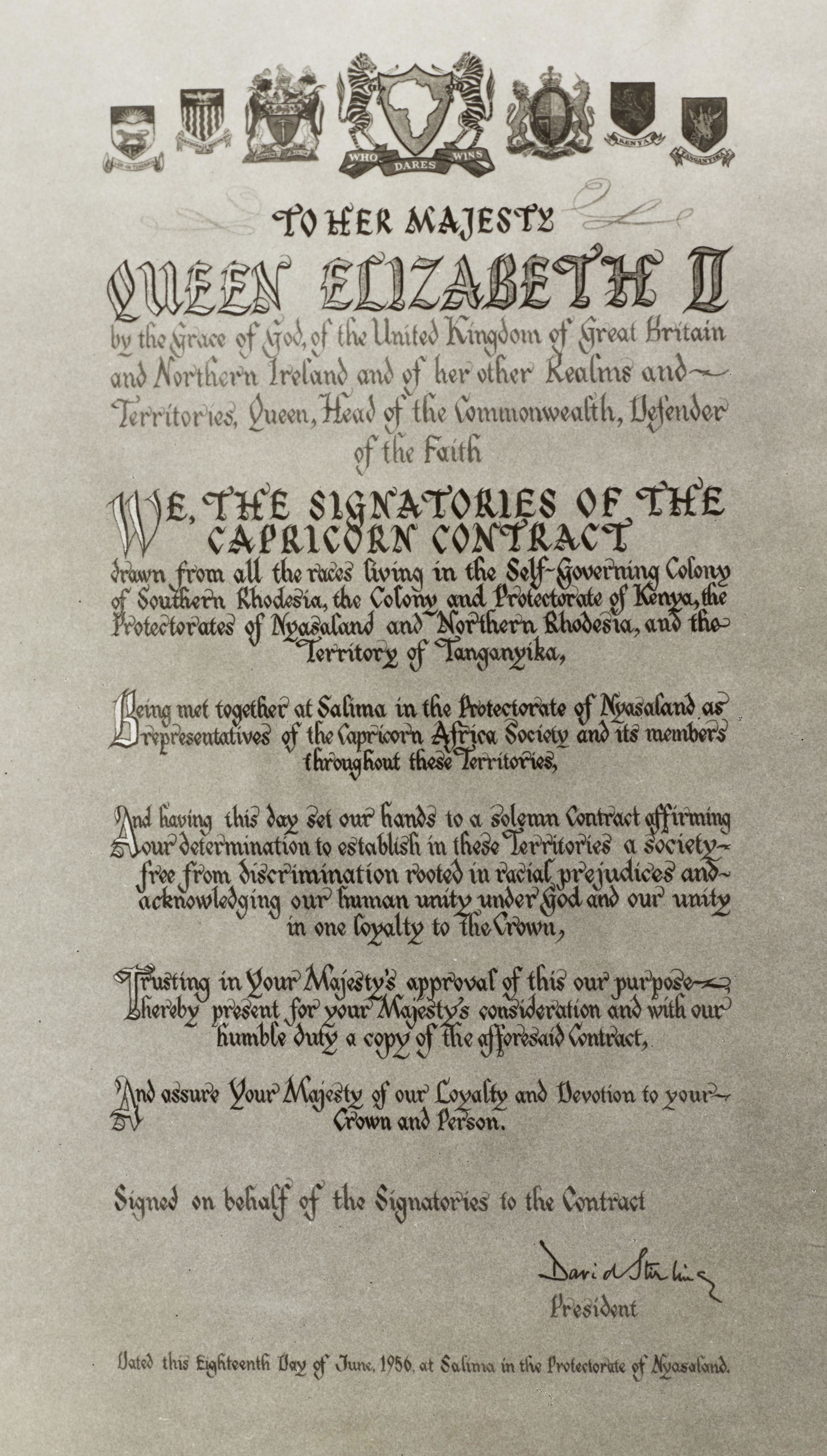

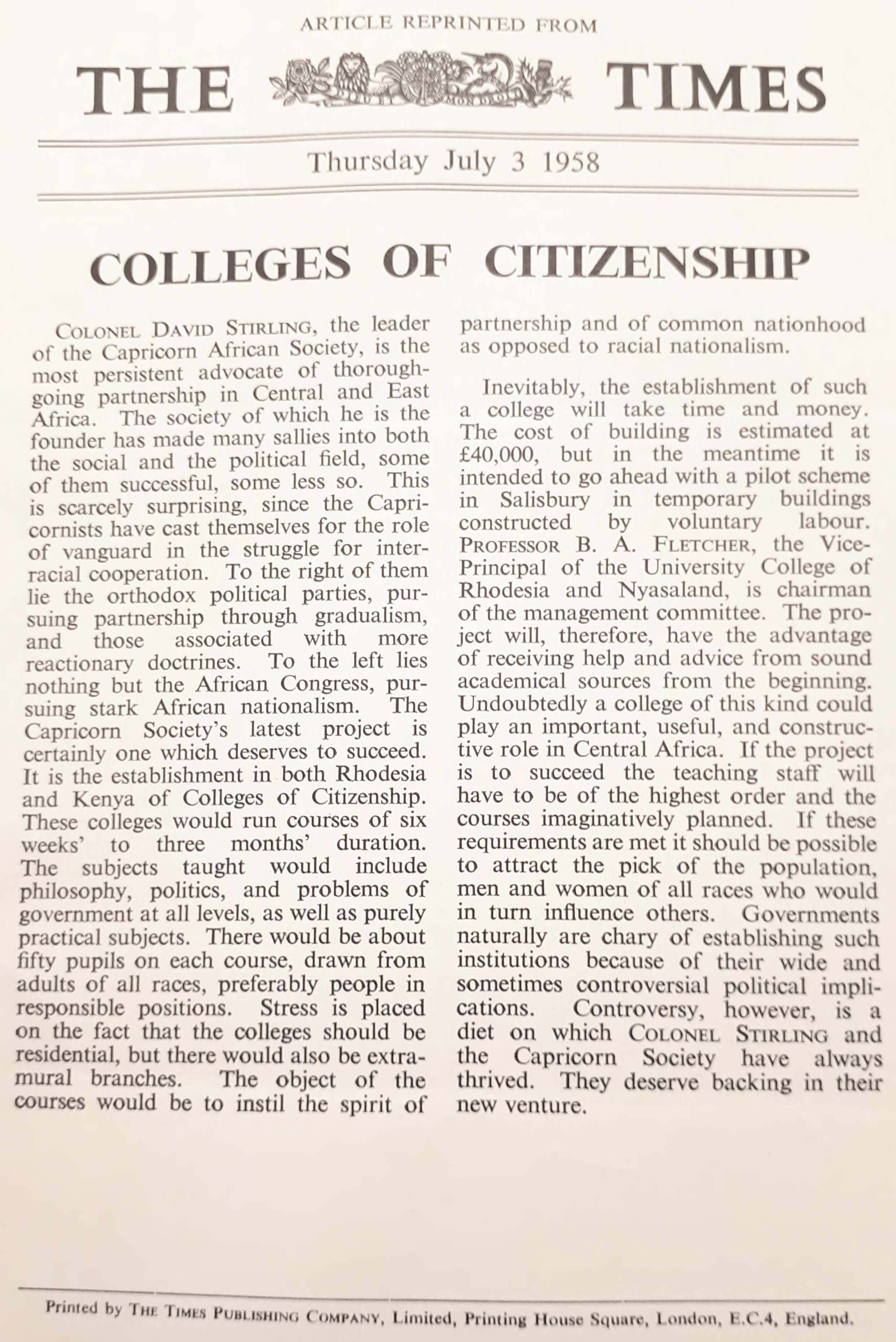

After a successful referendum in favour of Federation, the United Central Africa Association disbanded, and Mackay was offered a job as associate editor of the Rhodesian Farmer. He also joined the Interracial Association of Southern Rhodesia, founded by Hardwicke Holderness, a lawyer with the Southern Rhodesian firm, Scanlan and Holderness, and an MP in Garfield Todd's Government. Mackay helped move the Interracial Association's journal, Concord, the first multi-racial publication in Southern Rhodesia, from an idea into print.7 It was during his time at the Interracial Association of Southern Rhodesia that he met Colonel David Stirling, the founder of the Special Air Service (SAS). Mackay resigned from the Rhodesian Farmer after just nine months stating as his reason an 'unsolicited and quite out of the blue' 8 request from David Stirling to join Capricorn, an organisation whose objectives and purposes Mackay suggested he had sympathised with for many years. In his new role as Executive Director of Capricorn’s Central Africa branch, Mackay set up citizenship committees across Nyasaland and Southern Rhodesia, 9 building what he described as the 'most powerful political organisation in the Federation'.10 In June 1956, Mackay organised the first multi-racial convention of Capricorn's members at Salima. But the convention, while successful, simply confirmed his growing belief that the Capricorn Society was a 'well-meaning but inevitably implausible instrument for political improvement in the colony'.11 In October 1956, he resigned from the Capricorn Society.

JIMMY SKINNER

Co-founder of Tsopano

The Capricorn Society, 1956

excerpt from interview with Jimmy Skinner, 13.05.2019.

In 1958, Mackay refused a further offer of employment from David Stirling to be the first Bursar of the Capricorn Society's College of Citizenship, Ranche House College, in Salisbury. He had grown disillusioned with Stirling's paternalistic vision and in a letter to his mother, Mackay described Stirling's pursuit of him as a

"stalk" for the purpose of launching his latest scheme which, although flattering to the ego, has its irritant value also. Yesterday Stirling told me that I had said NO so firmly that he felt I was at least halfway to accepting the job.

Personal Correspondence, 1958

Following Capricorn, Mackay resumed his editing and publishing career with Rhodesian Farmer Publications out of which grew his own publishing company, Rhodesiana Limited. Publications at Rhodesiana Limited included various commercial undertakings from calendars to agricultural text books.

In 1959, alongside Jimmy Skinner, Mackay founded the monthly anti-Federation magazine, Tsopano, in response to biased and heavily censored press coverage during the Nyasaland Emergency (3 March 1959 - 16 June 1960), and to serve as a mouthpiece for those detained without trial during Operation Sunrise (3 - 5 March 1959). Mackay also provided support for the families of the political detainees at Gwelo (now Gweru) prison in Southern Rhodesia, and helped to set up Malawi News and the Malawi Press Limited, the first African-owned newspaper in Central Africa. Tsopano, with a circulation of 12,000, was absorbed into the Malawi News company under Doctor Hastings Banda and Aleke Banda.

Reports of his nationalist and journalistic activities had already brought Mackay to the attention of the intelligence services. But he was undeterred and in his recollections of the March of 7000, which took place in Salisbury in July 1960 in response to the illegal imprisonment of the African nationalist leaders, Leopold Takawira, Sketchley Samkange and Michael Mawema, and the poor treatment of African Rhodesians by the government, he wrote

The time for dabbling and stumbling was coming to an end. The emergencies in Nyasaland and Southern Rhodesia had concentrated the mind. My work on Tsopano had increasingly drawn me into a deeper understanding of African aspirations, and my growing association with the African nationalists had added a personal element, for they were my friends. Now, I believe, the march of the 7000 had made my commitment irrevocable, for to march is not to stumble, and I knew as we sat under the lights with the police cordon ahead that I was declaring alliance with those around me.

Mackay, p. 88

Mackay joined Joshua Nkomo's, National Democratic Party (NDP) in 1961. In the same year, with funds received from Kwame Nkrumah to aid the Malawi Congress Party's (MCP) election campaign, he purchased ten Land Rovers in his own name on behalf of the MCP. Together with Sketchley Samkange, he ferried the Land Rovers from Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, through Portuguese East Africa, to Limbe and Blantyre in Nyasaland. In April 1961, due to his criticism of the 'Lisbon dictatorship's rule over what it termed the overseas territories'12 in Tsopano, Mackay was prohibited entry to the Portuguese colonies. Later that year, he was charged under the Unlawful Organisations Act with continuing in membership of a banned organisation, the NDP, and under the Law and Order (Maintenance Act) with being in possession of subversive and prohibited documents. He was sentenced to six month's imprisonment, suspended for two years.

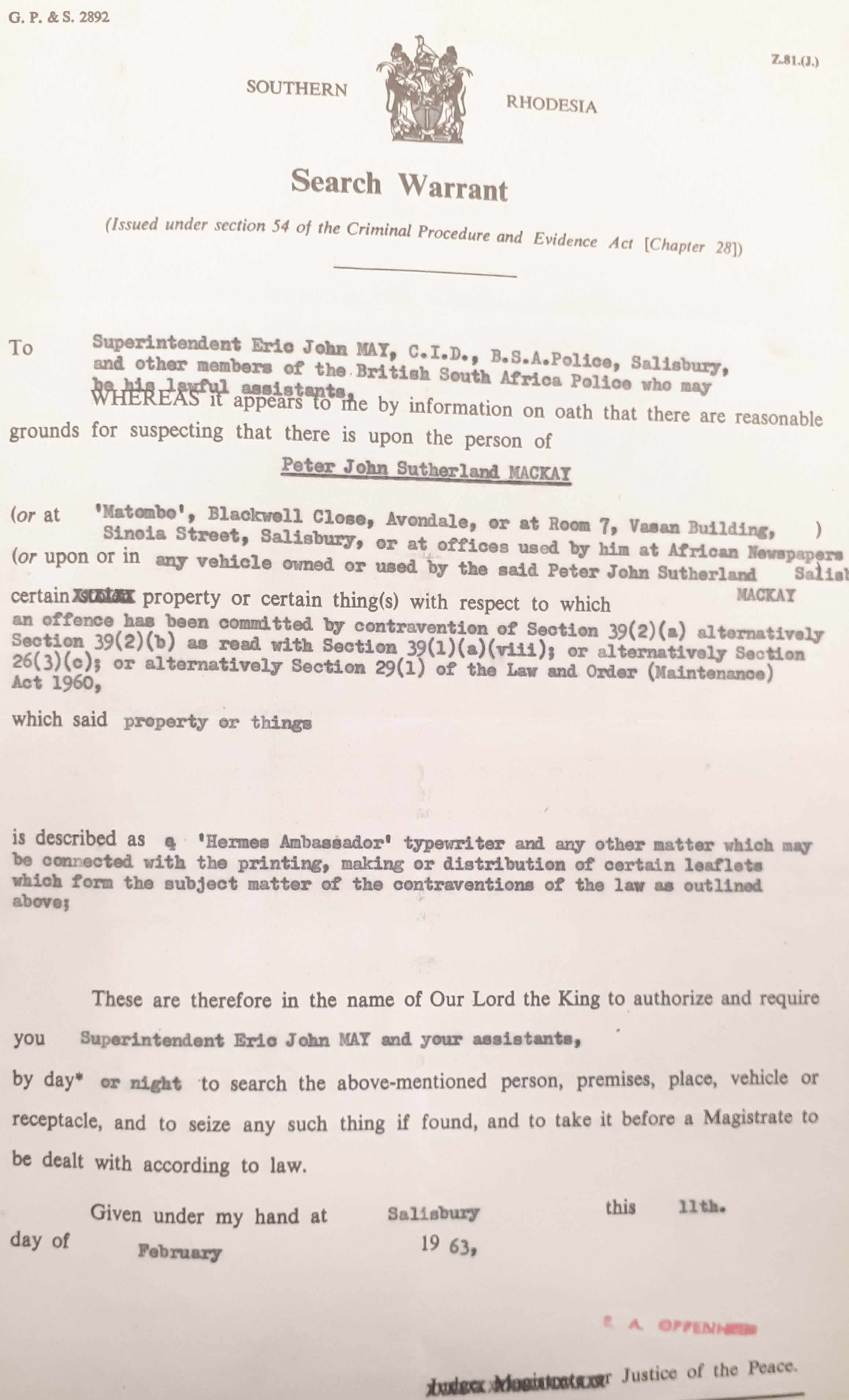

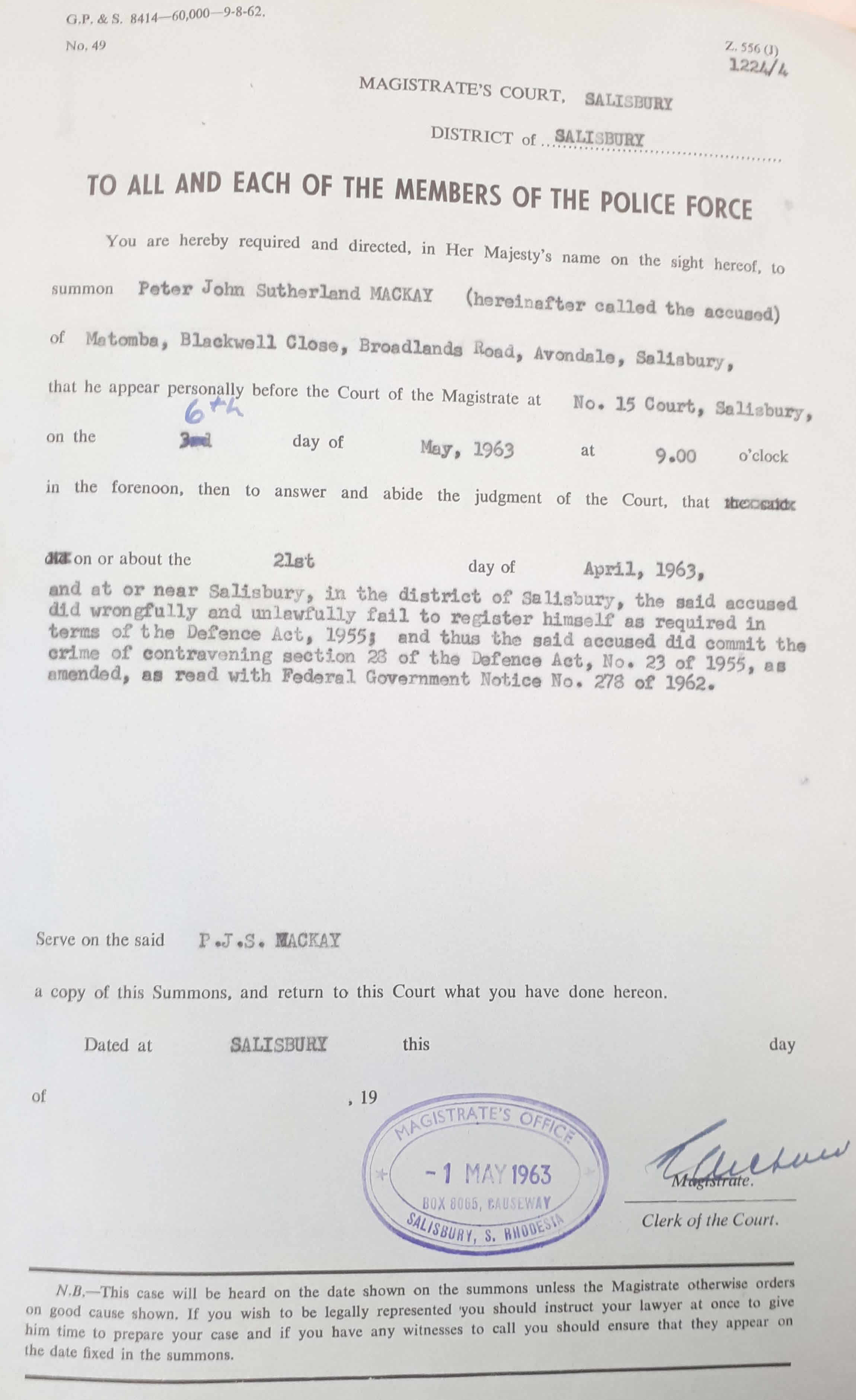

In 1962, Mackay attempted to launch another pro-nationalist publication, Chapupu II, in Salisbury, but the magazine was banned after its third issue on terms which ended the viability of Rhodesiana Limited. Further, he was prohibited from publishing under his name in any medium, which brought a halt to his career as a freelance journalist. Following a CID raid on his home and vehicle in February 1963, 13 Mackay was interviewed at the CID Headquarters in Salisbury and subsequently charged under the Federal Defence Act with refusing to register for service in the Rhodesian territorial force. He received a fine and an additional two-month's sentence, suspended. Following a second refusal to register for service, Mackay was imprisoned for four months (17.07.1963 - 06.10.1963).

Shortly after his release from prison, Mackay received a letter from Margaret Roberts Legum, secretary of the Joint Committee on the High Commission Territories. With the date of Northern Rhodesia's exit from the Federation approaching and with it, the opening of the border between the Bechuanaland Protectorate and Northern Rhodesia, the committee were concerned about the lack of infrastructure for accommodating the anticipated 'flood' of refugees from South Africa and the Portuguese colonies into Zambia. The committee requested his assistance with undertaking investigations into:

a. the transport question, overland, from Francistown over the river at Kasane to N.R. (Northern Rhodesia)

b. a possible transit camp on the N.R. side of the river

c. the first seeding of a settlement in N.R., possibly near Lusaka or on the Copperbelt - getting estimates for the land, buildings, agricultural possibilities etc.Margaret Legum to Peter Mackay, 28.10.1963

Mackay accepted the role and in conjunction with representatives from the Joint Committee, Amnesty International and the Northern Rhodesian government, preparations for the expected influx of refugees began.

EXILE

In 1964, Mackay returned to the newly independent Malawi to write and publish A Portrait of Malawi, the first publication commemorating the country’s independence from the African perspective. In December that year, he flew home to the UK to spend Christmas with his family for the first time since his arrival in Southern Rhodesia.

While attempting to return to Salisbury and despite already serving a prison sentence, Mackay was again charged under the Defence Act with refusing to register for military service and a bench warrant was issued for his arrest. Not willing to serve a further prison sentence and on the advice of James Chikerema and George Nyandoro, Mackay fled from his arrest warrant and received asylum in Zambia. On 12 November 1965, one day after the announcement of Ian Smith’s illegal Unilateral Declaration of Independence, Mackay renounced his Southern Rhodesian citizenship. In 1966 he purchased a property on the outskirts of Lusaka.

The place would meet my needs; more importantly it would meet the needs of the Zimbabwe African People's Union. I moved in together with six members of the party's military wing under the supervision of a 'commissar', Robson Manyika, and from that day the house became a ZAPU base, designated 'Camp C', later to be named by those who shared it 'Gonakupona', which is the place of peace.

Mackay, p. 281

During this time, Mackay became what he described as a foot-soldier under the command of leaders such as Dumiso Dabengwa, Head of the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) and James Chikerema, acting President of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). He continued his work with the Joint Commission, setting up the International Refugee Council of Zambia and mapping and running the Southern African refugee escape system from the White House Refugee Centre in Tati township, Francistown, along the Freedom Road through Botswana, across the Zambezi at Kazungula and on to the transit centre in Lusaka. When ZAPU and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) began preparing for armed conflict, Mackay breached his agreement with Botswana officials by ferrying guerrilla soldiers and carrying military equipment and explosives for use by ZIPRA.14 As a direct result of these trafficking activities, he was declared a prohibited immigrant to Botswana. Not wanting to bring disgrace on the Zambian government who had harboured him in exile, he resigned from the refugee council in 1967.

TREVOR GRUNDY

Journalist - BBC/Financial Times

Freedom Road & Politics

excerpt from interview with Trevor Grundy, 17.05.2019.

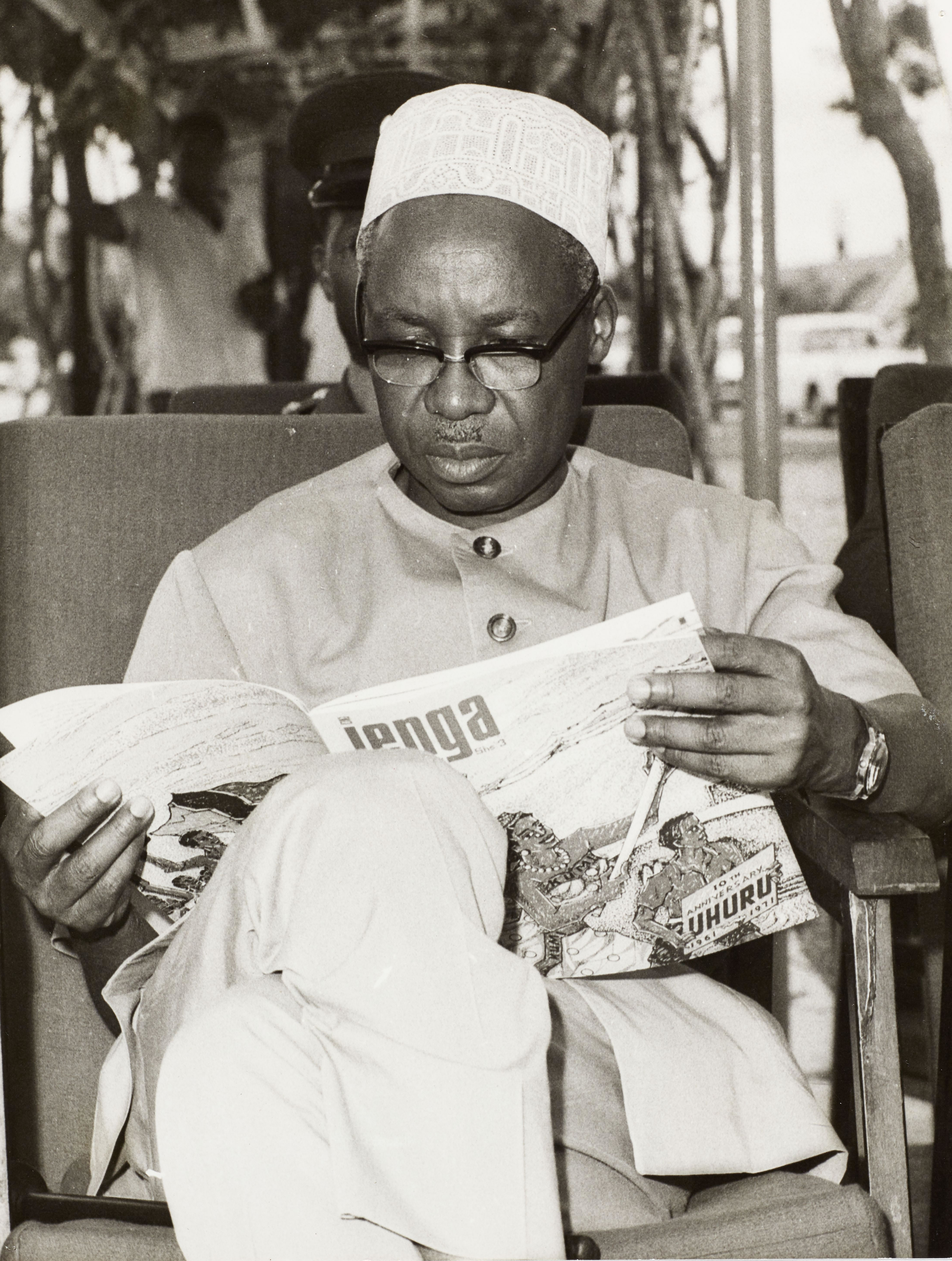

Mackay then travelled to Dar es Salaam at the request of Jimmy Skinner, where he worked for fifteen months, between 1967 and 1969, as chief publications officer for the National Development Corporation (NDC), developing the group's magazine, Jenga, which was primarily aimed at attracting foreign investment to Tanzania.

We are hoping to start an NDC Group magazine this year. I wondered whether you might be interested to produce the first number and train a local chap to take it on as a regular job, producing 2 or 3 issues a year. It would probably mean buzzing around the country and taking a few photographs, getting hold of some articles, adverts, etc. Also propaganda to tell people what the government is doing to develop the country through NDC and to give the NDC group a bit more cohesion.

Jimmy Skinner to Peter Mackay, 27.1.1967

During this period, Mackay remained active in the nationalist cause. As always, he was acutely aware of the ‘profound limitations to the part an outsider’15 could play in the liberation movement. Equally, he felt that these limitations did not excuse an outsider from opposing the injustices of European society. He continued to offer his services to nationalist leaders such as James Chikerema, Jason Moyo and Dumiso Dabengwa, sharing his military experience, analysing the Rhodesian Force’s military tactics and suggesting training programmes and field exercises for the freedom fighters. Mackay’s notes to Chikerema were based extensively on the training syllabi of the British army. He surmised that the Commander of the Rhodesian forces - a man who Mackay had trained during his commission as weapons instructor in Malta - would be employing the same tactics he had learned under Mackay’s instruction.16

In May of 1969, Mackay returned to Lusaka as manager of Oxford University Press. In addition, he agreed to represent the National Development Corporation in Zambia with the object of expanding trade between Tanzania and Zambia. In what would become a dictum that led to a life of perpetual poverty, he refused to accept a salary, suggesting that his work was a way of repaying his hospitality debt for the years spent in exile in Zambia. However, during his time with the Oxford University Press, Mackay’s work permit was revoked on the grounds that he had concealed his detainment from Zambian authorities.

By 1969, Mackay was already a prohibited immigrant in South Africa, Mozambique, Angola and Botswana and a wanted man in Southern Rhodesia. In response to the revocation of his work permit, he entreated Dr Kenneth Kaunda to intervene for fear of acquiring prohibited status in Zambia. His permit was reinstated, allowing him to remain in Zambia for another year during which time he assisted his comrades, Chikerema and Nyandoro in the formation of the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (FROLIZI).

Between 1972 and 1973, Mackay lived for a time at Glenartney Lodge in Comrie, Scotland. He then launched the Justice for Rhodesia Campaign from London and worked alongside Amnesty international to secure the release of the political detainees at Khami prison. He also began a protracted campaign in the House of Commons for the enforcement of sanctions against Southern Rhodesia.

Sanction breakers are Africa's enemies. They are also the enemies of international morality and law; and they are the enemies of political change in Zimbabwe.Personal Journal, 1974

PROFESSOR DAVID MOORE

Development Studies

University of Johannesburg

March 11 Movement - ZIPRA

excerpt from interview with David Moore, 11.05.2019.

In 1974, at the request of George Kahama, Director General of the Capital Development Authority, Mackay returned to Tanzania to continue work on the Dodoma Capital Development Programme, and to undertake photography and research for A Portrait of Dodoma.

On 20 November 1974, James Chikerema ordered Mackay back to Lusaka to deliver a public lecture at the UK High Commission, something Mackay had never been willing to do before.17 The British government wanted to build bridges with the nationalists and provide assistance to the freedom fighters, a sentiment which Mackay vehemently opposed in his speech because it ‘implied that Britain was willing to help others shed the blood that Britain itself did not have the courage to shed’, effectively ‘using Zimbabweans as cannon fodder to solve a problem of Britain’s own making’.18 In preparation for the Victoria Falls Conference in 1975, Mackay was tasked with drafting Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s speech and drawing up a variety of scenarios and outcomes to the meeting. But, after a telephone call from the London Observer requesting information on his role in the struggle caught Mackay off-guard, he was left with the familiar and uneasy feeling that he was again being monitored by the intelligence services and that his profile was ‘moving out of the low category’.19It was during his periods of self-exile in Tanzania and Zambia between 1974 and 1978, with no home, little money and the constant threat of deportation, that Mackay began to question his role in the nationalist movement. When asked about his willingness to come out into the open and take a leadership position, he refused stating that there was no point in replacing white rule in Southern Rhodesia with whites. But Mackay struggled to adjust to what he described as his ‘grey role’20 waiting on orders for speeches, documents and proposals during the Victoria Falls Conference, the Internal Settlement Agreement and Lancaster House. Mackay was a man of action and the static, covert administrative tasks in the lead up to independence combined with the increasing tensions between his nationalist friends left him frustrated. In response to another looming deportation order, he wrote

I can no longer go on as I am. I don't want the role of 'mystery man' or 'secret weapon'. I am more conscious than most of the limited role a white man can play and of the need to accept limitations. But surely not to the extent of corrupting the cause or destroying one’s own integrity.Journal Entry, September 1975.

In the wake of his disappointment with the Internal Settlement Agreement and the Transitional Government in 1978, Mackay questioned whether his personal principles and convictions were still aligned with those of the nationalist cause. ‘My duty’, he wrote

is to compensate for the wrongs done by my fellow Europeans in Rhodesia. My struggle is to remove European dominance, not to replace it with another form of European interference, no matter how well meaning. My politics are the politics of race, not of parties, and therefore I will leave when the Rhodesian Front is destroyed.

Journal Entry, November 1978.

But he found his loyalties increasingly tested. On the one hand he was determined to continue to oppose the Rhodesian Front but found he was unable to do so without also fighting his comrades who had joined the Transitional Government in alliance.21 Isolated in a Salisbury hotel during the negotiations, Mackay endured a period of intense unhappiness. In a letter to friend and confidante, Robert Oakeshott, he wrote

I draft speeches for others, those who will become leaders of our new Zimbabwe. The words echo back in the headlines and across the air waves. I have composed essays on land, justice, defence and foreign affairs for the manifesto. Writing these documents of significance demands both thought and discussion. This enforced solitude allows me an abundance of the former, but I am denied the latter. Three days have gone by without a single word said out loud.

Peter Mackay to Robert Oakeshott, 1979

The collapse of the Internal Settlement agreement came as a ‘great relief’22 to Mackay. In his journal, he wrote of the sudden and enormous potential for change in Zimbabwe. But the ensuing and unseemly scramble for top spot in the independent government left Mackay despondent. He found the determination of the nationalist leaders to put personal wealth and advancement before the liberation of the people of Zimbabwe disappointing.

The politics of race, in which I was entitled to play a part are giving way to the politics of African power in which I have no entitlement to play a part. Thus, I have retired from politics.

Journal Entry, 5 August 1979

Humanitarian Work

With Zimbabwe's independence in 1980, Mackay's convictions were formally amnestied under the Constitution of Zimbabwe. Having already evaluated the need for extensive humanitarian efforts in the Binga district on the shores of Lake Kariba and, with his usual efficiency and enthusiasm, Mackay devoted himself completely to the development of the area for the next fifteen years. He worked with the people of Nyaminyami and NGOs such as Oxfam, Save the Children and the Campaign for Female Education (CAMFED), training co-operatives and entrepreneurs, developing projects for the blind, building dams and pipelines and creating political mentorship programmes.23

The people of Omay had for long been isolated from the mainstream of national life. The first misfortune to befall them had been of the man-made variety, namely the construction of the Kariba dam and the blocking of the Zambezi river to inundate some 2000 square miles of the valley and flood an estimated 55,000 inhabitants out of their ancestral homes and land. The terrain to which the people of Nyaminyami were evacuated – Omay in Mashonaland West and neighbouring Binga in Matabeleland North – was a far cry from the rich alluvial soils of the Zambezi littoral, where two sometimes three crops a year could be raised. During the 60s and 70s the region became a no-go area as Rhodesian military forces stood guard against freedom fighters encroaching from Zambia.

Peter Mackay, ‘Friends of the people or foes of the state?’, Zimbabwean Independent, 2001

ANN COTTON OBE

Founder of CAMFED

Omay - Nyaminyami District

excerpt from interview with Ann Cotton, 14.05.2019.

Between September and October 1984, Mackay was appointed by the United Nations as Special Project Writer for the Dodoma Capital Development Authority (CDA). In this role he was required to establish a Public Relations and Publications unit in the CDA, assist with the preparation of the proposed Dodoma Film and complete a number of photography and publishing assignments.24

In 1994, Mackay retired from his work in Omay. He purchased a remote bungalow in Eagle Way, Marondera, a place he described as 'his first home in 31 years',25 where he completed the manuscript of We have Tomorrow: Stirrings in Africa 1959 - 1967. In April 2007, he was brutally attacked in his home by two burglars. But in customary Mackay fashion and with his unique ability for finding the humanity in every situation he concluded his recollection of the incident by writing, ‘at least a family will not go hungry tonight.’26

On the 17th April 2013, following a long period of illness, Peter Mackay died as he had lived, in poverty and obscurity, his prediction that he would remain in Africa for life, fulfilled.

I always feel guilty that you worked so hard and helped a lot with our independent Malawi. Most of those who knew the role you played hope and pray that someday, someone will see what you have done and that you will have a home somewhere within Central Africa.

Rose Chibambo to Peter Mackay, 07.07.1980

Despite his nomadic lifestyle, Mackay amassed an extraordinary collection of Africana comprising some 1200 books, maps and volumes, the Clatworthy/Tredgold collection, and original artwork and carvings.

It was his wish that his library be left to 'Her Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom for use at the British High Commissioner’s residence in Zimbabwe'. Due to space constraints, the collection was given to Arrupe College in Harare. The bulk of his archive was left to the University of Stirling, but the National Galleries Commission and National Archive of Zimbabwe also inherited some of his possessions. Peter left his body to the University of Zimbabwe for medical research.

Rupert Connell, 2019

1. Stirling Council Archives, '1-11 George Street Doune - Thomas Maclaren', 26 April, 2016.

visit page

2. Bourne, Christopher, 'Bourne Reunion, June 2008' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

3. War Office, 'Military Service Record of Captain Peter John Sutherland Mackay, 13 November 1948' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

4. Hodder-Williams, Richard, White Farmers in Rhodesia, 1890-1965: A History of the Marandellas District (London: Macmillan, 1983), pp. 187-189.

5. Mackay, Peter, 'Letter to Christine Mackay, 14.12.1952' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

6. Mackay, Peter, 'Letter to Christine Mackay, 1953' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

7. Mackay, Peter, We Have Tomorrow: Stirrings in Africa, 1959-1967 (Norwich: Michael Russell, 2008) p. 7.

8. Mackay, Peter, 'Letter to Rhodesian Farmer, 4.10.1954' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

9. Hughes, Richard, Capricorn: David Stirling’s Second African Campaign (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003) p. 102.

10. Mackay, Peter, 'Letter to Christine Mackay, 1955' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

11. Mackay, WHT, p. 73.

12. Mackay, WHT, p. 125.

13. Criminal Investigation Department, British South Africa Police, Salisbury, 'Search Warrant, 11 February 1963', Mackay Archive.

14. Mackay, WHT, pp. 318-26.

15. Mackay, Peter, 'Letter to Kenneth Kaunda, 1969' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

16. Mackay, Peter, 'Letter to James Chikerema, 1967' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

17. Trevor Grundy to Peter Mackay, 04.12.1974

18. Peter Mackay to Robert Oakeshott, 24.11.1974

19. Mackay, Peter, 'Journal entry, 09.08.1975', Mackay Archive.

20 Mackay, Peter, 'Journal Entry, August 1975', Mackay Archive.

21. Mackay, Peter, 'Journal Entry, November 1978', Mackay Archive.

22. Mackay, WHT, p. xvi.

23. Nyaminyami Rural District Council, ‘Omay Development Trust, 2014’, Mackay Archive.

24. United Nations, ‘Special Service Agreement, 09.01.1985’, in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.

25. Mackay, Peter, 'Journal Entry, 05.02.1994', Mackay Archive.

26. Mackay, Peter, 'Letter to Jimmy Skinner, April 2007' in Personal Correspondence, Mackay Archive.